On making peace with "the unsatisfying grunt labor" of writing, according to author Rick Bass

Thoughts on the spirituality of working at your craft, and fighting for what makes you feel free

I read Rick Bass’s prose for the first time in 2015 in a piece called, “The 50 Best First Sentences in Fiction.” His sentence stood out from all the others. Here it is (along with a little more prose):

An ice storm, following seven days of snow; the vast fields and drifts of snow turning to sheets of glazed ice that shine and shimmer blue in the moonlight as if the color is being fabricated not by the bending and absorption of light but by some chemical reaction within the glossy ice; as if the source of all blueness lies somewhere up here in the north—the core of it beneath one of those frozen fields; as if blue is a thing that emerges, in some parts of the world, from the soil itself, after the sun goes down.

Blue creeping up fissures and cracks from depths of several hundred feet; blue working its way up through the gleaming ribs of Ann’s buried dogs; blue trailing like smoke from the dogs’s empty eye sockets and nostrils—blue rising like smoke from chimneys until it reaches the surface and spreads laterally and becomes entombed, or trapped—but still alive, and smoky—within those moonstruck fields of ice.

Blue like a scent trapped in the ice, waiting for some soft release, some thawing, so that it can continue spreading.

—Rick Bass, “The Hermit’s Story”

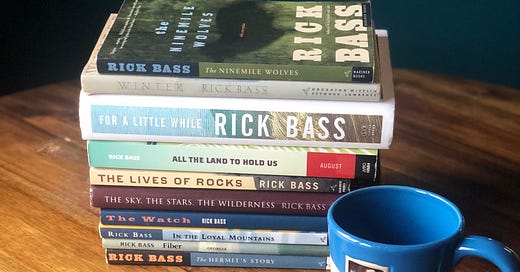

What caught my eye is that, amid all the others, that particular sentence looked more like a paragraph. But its elemental eeriness and dream-montage syntax is what made me buy the titular collection of short stories. I devoured them. Then, as many of his stories I could get my hand on.

Bass’s work had entered my life at the perfect time.

On writing lyrics that feel like short stories

I mark early 2015—around the time I started reading Bass’s work—as the beginning of doing the work on Redshift.

On February 2nd, 2015, after years of writer’s block, I’d finally fitted some words to a tune, “A Trusty Lie.” I’d compiled a batch of musical ideas that felt as if they hung together on an album, and as if they deserved to be fitted words themselves. I had a hunch of how I wanted everything to feel and sound—except for the words.

I didn’t know the direction I wanted to explore lyrically yet.

At the same time, I was reading a lot of Bass’s stories, whose paragraphs share the structure and shape of good song lyric. Bass builds sentences with simple, sturdy words and meaningful imagery. He makes you feel his characters by looking at these details the way they do. His paragraphs feel like verses, layered with details to see, smell, taste, touch, and hear. His gut-punch lines, the lines that end these paragraphs, read like choruses or refrains: more tell-y, more abstract- or feeling-forward.

I recognized this structure, this adherence to the rule of “you can’t tell unless you show first.” It was straight out of Pat Pattison’s “Writing Better Lyrics.” This style puts more weight into those gut-punch lines. And in addition to all of Bass’s filmic detail, those tell-y, gut-punchy lines often read like they were lifted out of old country songs; lines like “He thinks almost is real close, instead of real far” (from “A Hermit’s Story”).

Bass’s short stories felt like lyrics. I wondered if I could write lyrics that felt like short stories.

Over the 7 years it took to finish Redshift, I returned to Bass’s work often. His influence lingered, even after the lyrics were written. In early 2022, when I reached out to Manchester-based painter, David Bez, to describe the color I wanted him to capture in the cover art—that of blue moonlight on Michigan snow—I included that very first Bass sentence I read.

On “the danger of a writer knowing too well the direction you're going”

Bass’s influence on my work went beyond style to the practice of writing itself.

Along with Verlyn Klinkenborg—whose book “Several Short Sentences on Writing” I read like a bible before writing each morning—no one changed the way I thought about the work of writing like Rick Bass.

Through Bass and Klinkenborg, I was able to reframe what felt like writer’s block as just the work itself. Instead of sitting down hoping to be inspired and feeling like a failure if I wasn’t, I’d revisit the same strange and ineffable feeling or image, turning it over and over, like a geode I’d yet to crack open. I learned to stop insisting on knowing what point I wanted to make, and let the work make it instead.

Here’s Bass:

Bass: …If you come in wanting to prove something, or come in with a certain amount of knowledge beforehand, it's going to lean more towards nonfiction, and if you come in totally lost, just with some feeling, there's a good chance it's going to take off in the direction of fiction. And that's all there is to me.

Slovic: Does that tend to determine which genre you work in? As you sit down to write, you may not even have fixed your plans for one genre or another—it depends how definite your idea, your feeling, about the subject matter is.

Bass: Right. I sit down at the desk and I'm feeling something, and if I have a good idea what it is I'm feeling, it'll probably be nonfiction. That's not to say nonfiction doesn't have discovery or revelation, but more often than not these days in my nonfiction I'm just trying to say something that I feel already, that I know—I'm trying to save something, I'm trying to stop something, or I'm trying to celebrate something. I'm writing about something I'm familiar with. If I sit down just totally lost—if I just have a strange feeling or a strange idea, a strange mysterious emotion, then that's good fertile ground for fiction. And whether the elements or the characters in it are things or people I know or don't know, or whether it's things that I've done or haven't done, is irrelevant. It's more the feeling that I bring to the paper when I sit down, and that's about as far as I'd take it. So yeah, it's irrelevant and I think the more you talk about it, the more aware you become of it. … But again, that can be the very danger to a writer—knowing too well the direction you're going.

The satisfying part about finishing each song for Redshift was not saying exactly what I thought I wanted to say when I started writing it. It was following some mysterious feeling until I discovered a new way of understanding myself and connecting with the world.

On making peace and keeping on going

During my period writer’s block, I read a small but still cringy number of creative self-help books to get unblocked. I didn’t write shit during those years, so I think it’s fair to say those particular drugs didn’t work. For me, anyway.

What did help was this: When asked “Who is a writer?”, Bass responded with an answer I found (and still find) deeply calming, with no trace of self-helpin’, self-lovin’ woo woo nonsense, insofar as I can spot it.

Q: Who is a writer?

Bass: [S]omeone who’s made his or her peace with that 98:2 ratio of unsatisfying grunt labor to momentary gratification … and continues to labor onward. Knowing that even that 2% diminishes across time until essentially you approach a state of purity where you—regardless of publishability or acclaim—you keep working and you learn to treasure the challenges and obstacles and failures. Not treasure, but make your peace with it. And you keep on going. Not a lot of folks like that. But I’ve met some and really admire them.

Even still, hearing Bass say this again years later, I nod the same fatalistic, purse-lipped nod I recently nodded to the doctor who pointed to an X-ray of the hips he’d already repaired a few years back and told me something is, in fact, wrong again when I already knew that, I already knew it, damn it.

It’s the blunt truth. It’s the cold heart of the matter.

But isn’t it also kind of a relief to get the diagnosis? And rather than coming from someone trying to sell you some creative lifestyle brand, it’s spoken by someone whose lived it and has the body of work to prove it.

These are the people I listen to on matters of craft and creativity. Who “jump into work head first / without dallying in the shallows / and swim off with sure strokes / almost out of sight.” Who make peace and keep going.

On fighting for what makes you feel free

I spent 98% of my time making Redshift just… kinda… exploring. For seven years, these songs were secret wildernesses I could retreat to and explore whenever, wherever. Even if I didn’t discover anything new for weeks, months on end, the act of exploring its spaces became its own reward.

It’s June 21st, 2023. In two days, it’ll be four months since I released the album. Lately, it’s been hard to look away from the daily deluge of real-world horrors; hard to find the time and sense of economic and mental stability to go exploring. Lately, those uncommodified wilds feel surrounded by bulldozers, by villains encroaching each day on the time and space that brings joy and peace and meaning.

I return to Bass, a former petroleum geologist and environmental activist:

"If it's wild to your own heart, protect it. Preserve it. Love it. And fight for it, and dedicate yourself to it, whether it's a mountain range, your wife, your husband, or even (heaven forbid) your job. It doesn't matter if it's wild to anyone else: if it's what makes your heart sing, if it's what makes your days soar like a hawk in the summertime, then focus on it. Because for sure, it's wild, and if it's wild, it'll mean you're still free. No matter where you are."

I’m leaving this open note to my future self, in the hopes it may be of use to you too: Feeling blocked? Feeling lost? Feeling hopeless? Finding no time to trek through secret retreats of wild hope and eternal beauty? “Tossing rations to the sea?”

Make peace with it. Keep going (despite that awful 98:2 ratio). Do the unsatisfying grunt labor. Take solace from those who did the same. Eventually, one of them will be you. Eventually, you’ll find it easier to make peace and keep going because you’ve already done that. Eventually, you’ll feel better.

For a little while, anyway.