Deep Dive 01: Kill the part of you that cringes

Let he who has not been cringe cast the first ironically detached subtweet

Redshift took seven years to make. It took another ten months to release.

(Did you cringe reading that? I didn’t cringe when I first wrote it, but editing this now, I cringed a little bit. Ah, well.)

By its nature, Redshift was doomed for a drawn out production timeline: My initial idea was a “survival guide for your 20s” and, well, first, I had to survive my 20s.

But in addition to working through the shame, doubt, fear, and despair required to make it out of my 20s, I had to work through those feelings in relation to my first work of art. I submit my use of that word just now as evidence of my own progress with regard to the latter. Throughout most of the writing process for the album, “art” was a word I could only speak, when referring to my work, with ironic detachment. I’d preemptively shield myself in conversation by speaking about my “art” in a tone best conveyed via oNe GiF iN pArTiCuLaR.

I spent days/weeks/months/years mulling over questions from a mob of nagging voices in my head: Would a real artist take this long to make something? Would a real artist have to work this hard? Would a real artist have a day job? Wouldn’t a real artist sleep in a van? Under a bridge? Live off grass and drippings from the ceiling? Rather starve? Rather die?

These are the eddies of neuroses a larval artist can easily get caught in. They’re useless at best, harmful at worst. Mostly, they’re a nuisance. Because they get in the way of the important questions, which are, of course, the ones you should be asking of your work—er, your art—itself.

I am cringe, but I am free

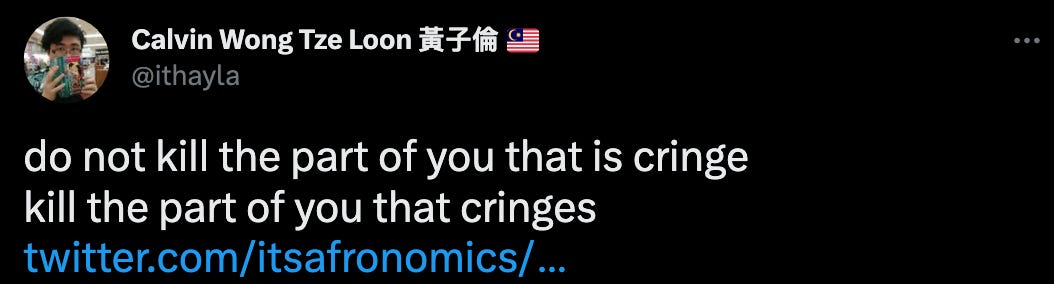

Last summer, shortly after sending away all the tracks to be mixed, and while prepping for the album’s release, I saw this reply to a since-deleted question. The original tweet asked, “People in your 30s, what advice would you give to people in their 20s?” This response stuck with me:

That was June 2022. With the work of making the album done, I felt a new variant of cringe mutating inside me: It was not the embarrassing swath of hours sunk into the unsatisfying grunt labor of making art that was causing me to cringe, but rather the thought of having to talk about the songs, of—buhhh—promoting them. This variant of cringe was vicarious: it was the not-quite-hidden wince I would picture on the faces of old friends, family members, co-workers, people from my hometown, and/or strangers when I imagined them seeing me talk openly about my ArTwOrK—ah, shit, I’m doing it again.

It’s June 1st, 2023. I’m a little over three months removed from releasing Redshift, and in some ways I’m back where I started in 2015. But devotees of the Hero’s Journey rest easy: I have indeed returned home, changed.

I still often feel that making songs, and taking so long to do it, and talking about and performing them, and sharing them, and—yes—starting a Substack to self-indulgently blog about all this is cringe. It’s just that—unlike in my 20s when the thought of “being cringe” could kill the wind in my creative sails for weeks—I don’t let that feeling get in the way of making stuff for longer than a day or two.

A few days ago, I saw another tweet about this topic from Jane Schoenbrun, writer/director of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair. I feel that they’ve expressed much more succinctly what I’m trying to get at here. (NOTE: that movie has been haunting me for months, and is one of the things that motivated me to switch to Substack: I’ll share my essay on it soon).

In my 20s, I was guilty of ironic detachment. But I can confess now it was just preventative posturing, a way of bracing for the potential impact of failure, of avoiding being seen as cringey. If you’re honest about having poured yourself into something and it bombs or it turns out to be kinda meh or it goes ignored by old friends, family members, co-workers, people from your hometown, and/or strangers, you can pretend that, actually, you never cared in the first place—lmao WOW you thought I actually CARED?

Fuck that. That’s just suicide in slow motion.

Breaking the Cycle of Cringe™

A few weeks back, I watched “Running With Our Eyes Closed,” which documents Jason Isbell’s work on his album, Reunions.

Isbell put out Reunions on May 15th, 2020. Those were still the early days of lockdown, so he had to play his album release show over Zoom. Between songs, addressing his virtual audience, he spoke about putting out such a personal, carefully crafted album knowing he wouldn’t be able to properly promote it:

“It’s weird as shit. But it would feel weirder to not put a record out. When I make a record, I make it about my life and how my life is then. And my life changes, so I don’t want to wait a year and then talk about what my life was like.”

I aim to create like that. It’s part of why I want to write and share cringey, naked-feeling pieces like this. Because while making Redshift, that approach to writing was inconceivable to me.

I took ages to assemble each song for Redshift. Each was its own a ship in a bottle. And I fixated on the notion that whatever was going into that bottle needed to fit together perfectly, correctly. Again, by the sheer nature of the album’s concept, I felt like I couldn’t allow myself messy expressions of something ephemeral and immediate. I needed to be right.

This “need to be right” is part of what I was getting at in one of the first songs I worked on that I felt belonged on the album, “Sleeveless Hearts.” In the context of this post, anyway, the lyrics read to me as an expression of the Cycle of Cringe™. There’s the rising action of having the audacity to believe in your own ideas and express your feelings with conviction, and the falling action of waking up the next day feeling mortified that you did that—GOD. WHY.

In my 20s, cringe was the zero-sum outcome of recognizing a flaw in an expressed feeling (a flaw in a feeling!). In my 30s, cringe feels more like a unit of measurement—the amount of dissonance between two or more contrasting feelings about the same subject.

It’s the amount of space, for example, between the pride and excitement I feel when finishing a song that I feel I nailed, and the mortification and doubt I feel when I have to talk about or perform that song. Part of growing, both as a person and as an artist, is about accepting one’s capacity to feel multiple ways about the same thing. And, in general, about letting yourself do something that might make you look stupid/sincere/heartfelt/mid/[INSERT THING YOU FIND CRINGEY WHEN OTHERS DO IT].

I’ve learned that how I feel about my work art depends on the emotional weather that day. Some days I believe in it. Others, I don’t. It’s not a thing I have any control over. The biggest lesson I learned by finishing Redshift was to keep doing the work, even on the days where it seems as if all those hours wont lead to anything meaningful.

A few weeks back, I sketched out an outline for a new album and noticed many of the same themes and subjects I wrote about for Redshift. But I feel differently now. I see new facets I want to shape and polish. And I want to write about how my life is now, right or wrong; messily, imperfectly. Cringe or not.

1. I’ve always loved your writing, this is no exception

2. I really enjoy the concept of “emotional weather.” It’s a feeling I was trying to describe to someone earlier today but I think I’ll use your words from now on.