Mike Viola’s “Paul McCarthy” is an open love letter to classic rock

An album review (sorta), but mostly a look at the craft of veteran songwriter/producer operating at the top of his game

Mike Viola has a problem.

He’s admitted it, on record, twice now.

The man cannot stop drowning in electric guitars and classic rock.

As he did on 2018’s The American Egypt and 2020’s Godmuffin, Viola borrows gleefully from the golden eras of guitar-driven rock. On his latest album, Paul McCarthy, he delivers nine songs as fresh feeling as they are sun-faded—the kind of lost-gem LP you hope to find any time you go digging through milk crates in a record shop.

And yet—as ever across his discography—Viola’s vintage-sounding songs never tip into pastiche or nostalgic rehashing. Write a riff that rips as hard as the one that kicks off “Scientist Alexis,” and you’ll make a recovering smug hipster like myself forget every time he ever echoed a line about the supposed death of rock guitar.

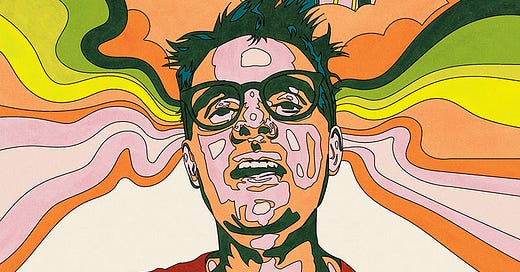

If McCarthy’s cover art doesn’t make it clear, its title should give away the game: Viola wants you to notice the artists and eras he’s flirting with.

Notice! (an incomplete list):

The gleaming “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper”-esque cascade of guitar in the choruses; the ghostly, minor-key-ified interpolation of “Boys of Summer” in the turnaround after the first chorus; and the Black Sabbath hyper-shuffle freakout and Iommi-an guitar bends in the bridge of “Water Makes Me Sick”

The soft, Peter Gabriel- or Toto-esque synths in “Love Letters from a Childhood Sweetheart”

The clacking of a sidesticked snare combining with spidery, chorused guitars a la Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” in the opening bars of “I Think I Thought Forever Proof”

The galloping “Get Back”-style start up of “You Put The Light Back In My Face,” giving way to riffs straight outta Bad Company or Big Star or Thin Lizzy or—ah, nevermind: too busy singing along

For going on three decades, Viola’s been making a career out of writing and performing his own music, penning songs for movies like Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, sitting in as a studio musician, and producing records for artists like J.S. Ondara, Jenny Lewis, and Andrew Bird.

I wanted to take a closer look at how he does it all so maddeningly well.

Doctors HATE him: the four elements of Mike Viola’s music

#1) Develop an ace singing voice (but use it to sing as someone else)

There’s a decent chance you’ve heard his voice before, even if you think you haven’t. But if you haven’t, the timbre of Viola’s voice is the first element of his songs you’re likely to notice.

Viola maintains a gravel and warmth in his voice no matter what register he’s in. It’s there as he helters and skelters up to the top of his range in the chorus of “Torp.” It’s there as he flips into a craggy falsetto (not unlike that of the album’s sorta-eponymous figure) on the torch-song refrain of the album’s eponymous song.

But Viola’s secret trick for dialing in the right tone in his voice is that he imagines himself singing as someone else. For example, in order to achieve the right amount of brassiness and squeeze in the chorus of “All You Can Eat” from Godmuffin, he had to picture himself singing as someone else.

You’ll never guess the Shyamalan-like reveal of who that someone is:

#2) Woodshed your song like a craftsman …

If Viola’s voice as a singer is his gift, his voice as a songwriter is the culmination of a lifetime of studying the form.

His endless repertoire of techniques have enabled him to produce a catalog of wildly different songs, each as sturdy as a finely crafted coffee table: deceptively simple, but built to last.

When he strips his tunes down to a lone guitar, Viola reveals his artistry: the way his vertical melodies leap acrobatically across multiple measures of his verses; the way his chord progressions (familiar seeming at first) are neatly fitted together with cleverly borrowed, voice-led passing chords; the way his lyrics (full of humor, poignancy, and fresh, modern-day imagery) remain free of filler and cliché.

#3) … but don’t over-polish it with production

Some songwriter/producers separate “the writing of the song” from “the recording of the song.” Viola has said that producing his own music is part of the writing process, that both processes inform each other.

Viola eliminates the clutter in his productions by only keeping an instrument if the song would lose something vital were it taken away. He’s able to create seemingly inexhaustible varieties of groove out of three simple ingredients: drums, guitar, and bass.

He must be deathly allergic to studio trickery, or at least extremely intolerant of needless ornamentation. He only adds a glaze of Juno synth or backing vocals when absolutely necessary. He purports to rarely use compression, favoring raw sounds with a live feel over isolated tracks that are studio-perfected but lifeless at their core.

#4) Arrange your song with care, but never with fuss

Viola’s arrangements remain interesting the whole way through, but the way he develops his songs is rarely flashy or finicky. He knows the emotional apex in every section, but he’s reserved about how intense the spotlight is that he throws on it.

If Coldplay’s signature move is knowing exactly how long to hold off till the drums come thundering in to tell you “THIS IS THE SONG’S CLIMAX,” Viola’s signature moves are subtler: He knows exactly when to throw a new element or subtle change into the arrangement: a shift in dynamics; an altered, extended, or colorfully voiced chord; a bass note you haven’t heard before under a chord progression you’ve heard multiple times.

His arrangements are all about balance. For example, note the difference in quality between verse and chorus on “Water Makes Me Sick,” and notice how their being side-by-side makes the other more impactful: The swaggering riff that drives the verses sticks to a motif of repetitive, pentatonic notes, allowing the harmony in the guitar chords to bloom in technicolor on the line “shattered in a million little pieces.”

Album highlight: “Love Letters From a Childhood Sweetheart”

I forget to breathe when I listen to this song.

Into four-and-a-half minutes—with astonishing degrees of empathy and grace—Viola fits a novel: the joy of falling in love with someone and the unhealable pain of losing them to cancer; the hope that renews when someone finds love again, if they’re able, and the preternatural resilience of those who carry on, knowing they’re not.

Viola’s lyrics float omnisciently, following a thread of fate that intertwines the hearts of three generations of people: himself; his children; his current spouse; his late wife; and his former mother-in-law, to whom the song is tenderly addressed.

Notice that Mike Viola the Producer doesn’t use a stronger take from Mike Viola the Singer, whose otherwise unfaltering voice hangs by a fingernail onto the note that’s barely there the first time he croaks out the word “kid.” Notice how Viola the Songwriter inverts that C chord at the end of each chorus—a sob caught in the chest, choked back before you hope anyone sees. Notice how Viola the Arranger lets his electric guitar disappear into mix in the final chorus—the ghost of a loved one fading away, as if forgotten for the final time—before a new glowing guitar line appears, reincarnated now in the right speaker now as a beam of morning sunlight to warm the final lines. Notice the line Viola the Lyricist repeats in each verse (“You lost a kid”), and how each repetition gleans meaning from a montage of images that would seem mundane were they not juxtaposed so devastatingly against one another.

All of these elements of Viola’s craft are on display here—his lyricism, his songcraft, his production, his arrangements—and combine to form something greater than the sum of their parts. Something human. Something beyond human. Something that, if not for song, may very well be ineffable.

A song like “Love Letters” is the closest thing to a real-life magic as it gets for me. It’s better than magic: There’s nothing illusory or deceptive about it.

It does require some dexterity, though. And like a master magician, Viola pulls off his trick in plain sight. He lets you get lost in the song, lets your mind wander.

But he knows his craft: he knows the exact moment he’s going to break your heart.

When Kim died, I moved away I fell in love again But you, you clean the kitchen You fold the laundry, you lost a kid And while we live and lose track of the days Everything that mattered begins to fade away But in my heart I swear to God A tree is growing, it’s branches reaching for you Now, trying to connect Love letters from a childhood sweetheart Now, trying to connect Love letters from a childhood sweetheart

“[Guitar’s] forever, and that’s the way it’s always been”

When I saw him live back in April, Viola asked the audience to clap along to one of his songs, but “only in the chorus, ‘cuz if you do it in the verse, it sucks.” His bassist asked how someone would know when to start clapping if they didn’t know the song and when its chorus started. “It’s obvious,” Viola said, turning to the crowd. “The voice leading will lead you there.”

Sometimes when I’m woodshedding songs in the studio, I catch myself: I start feeling bored by guitar. I try to discover undiscovered sounds. I create unnecessarily weird song structures, forget the rules and techniques that have stood the test of time for a reason, make unexpected turns, just fuckin’ ‘cuz, man. I try to make something that will impress people, rather than move them.

That’s all well and fine now and then. But a songwriter like Mike Viola reminds me to forget all that shit: It’s more impressive to do the latter.

Mike Viola is on tour this fall, and playing at Schubas Tavern in Chicago on October 22nd. See you there?